Don't know?

Have you ever felt like you don't know anything about what's in front of you when you're nature journaling? That there's no way to fill a nature journal page with observations or even one question? Here are 10 tips to help you push through these hurdles when you don't know:

- What to do

- Your subject

- How to think of questions, or

- What's wrong

If you prefer to watch the video version of this you can find it here:

What to do

If you don't have any ideas on what to nature journal then choosing from a prompt list can help. Sometimes getting started is the hardest part, so to push past the blank page paralysis, and for other ideas for choosing what to focus on, see my previous post:

However, let's consider what to do when you want to keep going and aren't sure how to continue. Let's say you're halfway through a page and you've done a drawing and some writing but you're not sure what else you can add to finish the page. It doesn't need to be finished but if you want to keep exploring, what are the options?

This is the moment to take a step back and try a new perspective or exercise. The zoom in, zoom out exercise is fantastic for forcing you to look at the same subject again with fresh eyes. If you have a magnifying glass or microscope what do you see now? Or zoom out and consider the surroundings - what else is nearby that might affect this specimen?

Other exercises to refresh what you're seeing include finding a different specimen of the same species then compare and contrast to the original one. Or exploring a different sense - touch, sound and taste usually get forgotten. Could you do a dissection from different points? Or make a question trail by picking one you've asked and following that line of thinking - is it possible to come up with a hypothesis or discover the answer by further observation? What other related questions come up?

You can also do some research and add more information later. Which brings me to the next part:

Your subject

There probably won't be many times when nature journaling that you will know everything about the subject. Even experts still find more to discover and they've been immersed in their research niche for years. So what to do when you don't know what's in front of you?

I'd say this actually a good place to be when nature journaling. It's so easy to fall into the trap of "I know this" when you might only have a few bits of information and then not bother continuing to use your curiosity to keep exploring. So firstly, accept that it's OK to not know.

In school there is a lot of negativity around not having the correct answer or solution. This trains students to remain quiet or not even attempt something if they don't have the confidence of being right. However, this shouldn't be the case. It's normal to not know everything (yes, even as adults!) and the reason for doing nature journaling is hopefully to learn more about our world. This is good practice for sitting with, and ultimately accepting, that discomfort of not knowing. It's better to have a guess and be wrong, than never wonder in fear of being wrong.

Of course that's not to say that we should always remain in the dark - go and find the answer or do some research if you're so inclined! If you discover you were wrong, then don't take it as a slight on you personally, instead as something new learned. Leaving something unknown is equally fine. What counts is that you considered and gave thought to it in the first place - practicing that curiosity.

So to help discover information about your subject you can start by noting down observations. Give as best a description as you can. This is after all how answers are found in the first place! That information might give enough clues to find the answer in a book or online using Google, or for others to help you, for instance friends, local guides or experts. One handy tool to help identify nature is the iNaturalist app, that not only gives you information about what you saw, but can then be used by scientists around the world in their research.

How to think of questions

If you're anything like me then it can be hard to think of questions. Or at least interesting questions. What do you do when you've asked what something is and what's happening then you're left not knowing what else to ask?

Continuing to look more at your subject might help, but usually I find that's when I start thinking to myself that I'm done, or this is silly or notice that I'm hungry or itchy etc. This is the moment your brain wants to give up but when you are actually so close to making those new discoveries and interesting questions! Again, trying a new perspective or exercise can promote new questions to come to mind.

Children are excellent questioners. Listen to what they're asking (and take it seriously). Sometimes the silliest of questions might actually lead close to the truth, or at least down some interesting rabbit holes of discovery. Dare to ask silly questions. Keep practicing and with any skill it will get easier with time.

What's wrong

Finally, you might at one stage look at your work and notice that something's not right, but are unsure of what exactly, or how to fix it. Perhaps you'd like to try someone else's technique or layout but don't know how to go about it?

Asking for feedback can be forbidding because you're offering a part of yourself, something personal that you might have spent a considerable amount of time or effort on. No one likes to be told their work is no good, but remember as well that you are more than just that page or your drawing or journaling skills.

It helps to be specific when asking for feedback. You want to improve, so the most useful feedback will apply directly towards that goal. If you think the proportion or anatomy is off, ask where it might be and how to fix it (e.g. make head larger). Just asking if something "is good" will more likely give you a vague, non-helpful response back.

Asking someone "How did you do that?" shows you appreciate what they've done and most people are more than happy to then offer advice, if you're willing to listen. It's a great way to share ideas and pages of your nature journal. So don't be scared to ask others or look online and "steal" ideas from other people to try out in your nature journal. Watching other people while they work or looking at their pages can help you see your own mistakes and stimulate new approaches to try for next time.

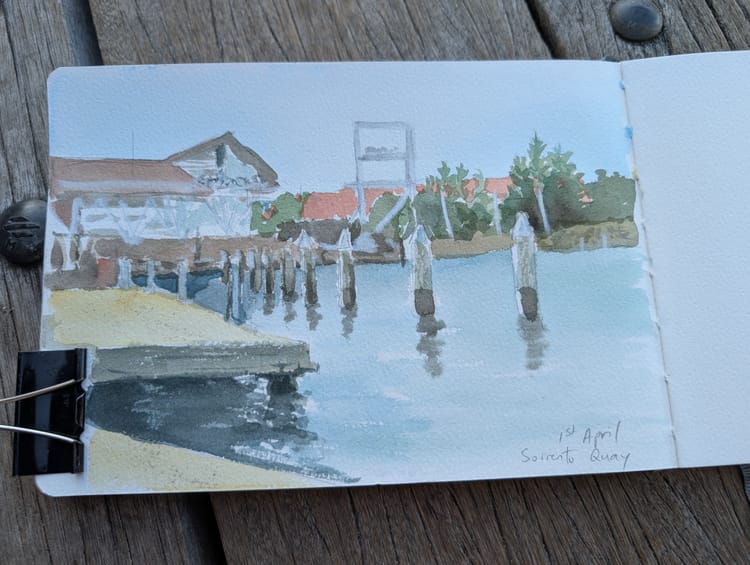

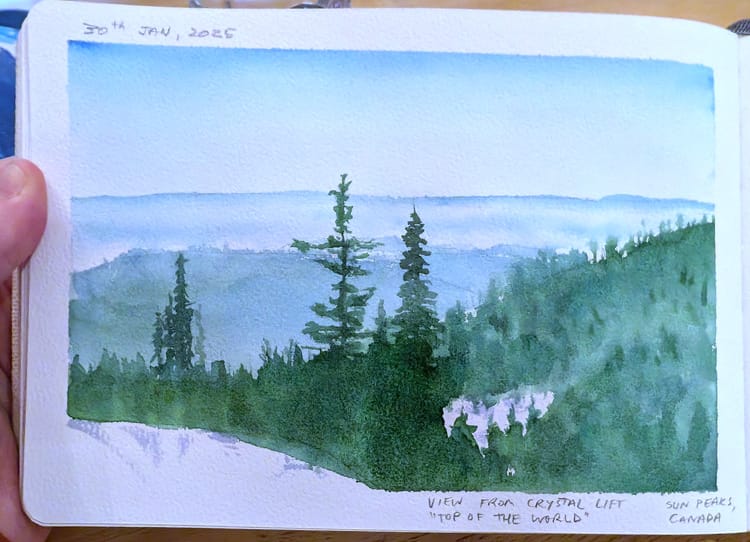

These tips require you to be brave in a lot of ways, however that's what is necessary when facing the unknown. Keep in mind, it might not actually be as bad as you think and with the right support soon enough you'll be finishing sketchbooks and seeing leaps in growth!

Do you have a question you like to ask when nature journaling? Have you got any tips for what to do when you don't know something?

Extra resources

- Zoom in - zoom out handout: https://www.oxbow.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Oxbow-Second-Journal-Challenge-Prompt_-Zoom-In.pdf

Member discussion